In these days of near super-sonic air travel, getting around by “snail-rail” (train) is nearly all but forgotten. However, for the African-American community, rail travel is held in great regard because it was once a way of achieving something akin to middle-class status. To truly appreciate this fondness for the “snail-rail,” perhaps a bit of history is in order.

A Historical Perspective

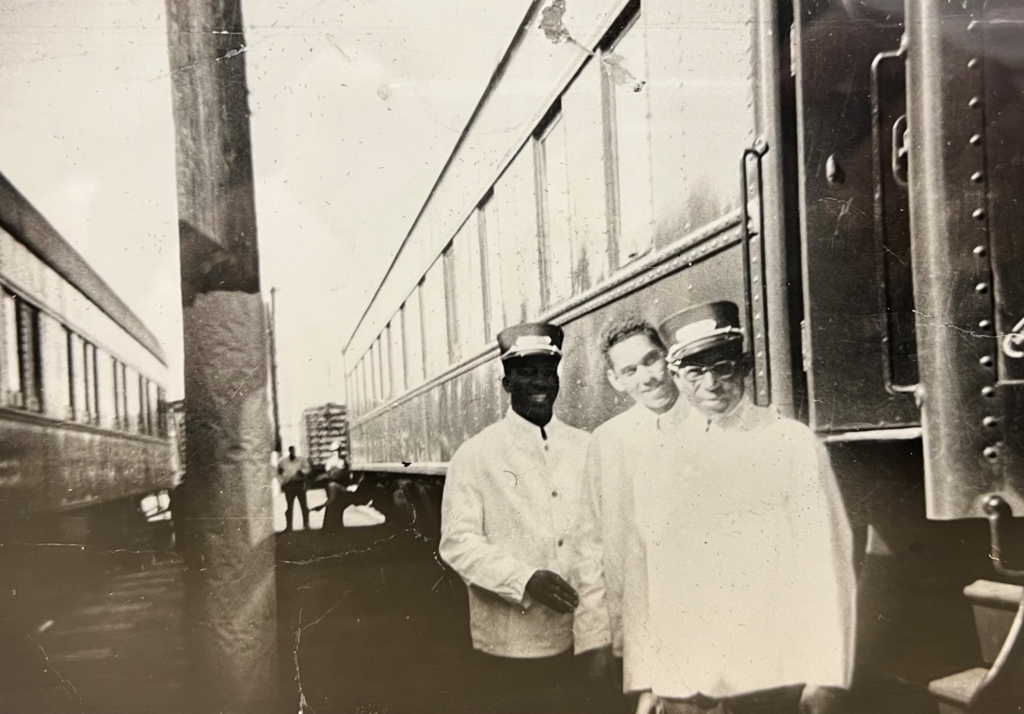

To ensure upper-class rail travelers’ comfort, entrepreneur George Pullman designed rail cars in which the journeyers could sleep, eat, and play in luxurious, home-like comfort—and to make the atmosphere complete, he sought out and employed former slaves to work in his “sleeper cars.”

Those employees’ jobs were to perform whatever tasks necessary—cleaning, making beds, serving meals, etc. Instead of being designated as “servants,” they were called “porters,” or more specifically “Pullman Porters.” Such positions and arrangements started shortly after the end of the American Civil War and served American railroads for 100 years—from the late 1860s until late into the 20th century.

While the Pullman Porters’ work was steady, the pay was minimal while also being very demanding and whimsical—depending on the idiosyncrasies of the Porters’ individual White supervisors. Therefore, after decades of abuse and discrimination, in the 1920s, a group of disgruntled Pullman Porters in New York City organized and sought the help of African-American labor leader and civil rights activist, Mr. A. Philip Randolph. Randolph had earned recognition as a strong advocate of the rights of African-American working men and women to form an independent union, representing and reflecting their unique interests. Through Mr. Randolph’s efforts, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) came into existence in August 1925—the first African-American-led labor union. Mr. Randolph patiently fought for and won a collective bargaining agreement with the Pullman Company in 1937. (Mr. Randolph later used his experience in confronting the Pullman Company to help organize the others in the fight for civil rights in the 1940s and 1950s.)

While the Pullman Porters’ work was steady, the pay was minimal while also being very demanding and whimsical—depending on the idiosyncrasies of the Porters’ individual White supervisors. Therefore, after decades of abuse and discrimination, in the 1920s, a group of disgruntled Pullman Porters in New York City organized and sought the help of African-American labor leader and civil rights activist, Mr. A. Philip Randolph. Randolph had earned recognition as a strong advocate of the rights of African-American working men and women to form an independent union, representing and reflecting their unique interests. Through Mr. Randolph’s efforts, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) came into existence in August 1925—the first African-American-led labor union. Mr. Randolph patiently fought for and won a collective bargaining agreement with the Pullman Company in 1937. (Mr. Randolph later used his experience in confronting the Pullman Company to help organize the others in the fight for civil rights in the 1940s and 1950s.)

After gaining recognition as a bona fide union, this distinctive and distinguished uniformed group of African-American train workers fought tirelessly for their rights. The resulting safe and steady work allowed tens of thousands of African-Americans to personally experience middle-class life. Over time, the Porters were able to individually combine their improved, albeit still relatively meager, salaries with gratuities. Doing so allowed them to save and put their children and grandchildren through college, which in turn helped them attain middle-class status.

As train service declined in the 1960s and the Civil Rights movement grew, the number of Pullman Porters dwindled. It is believed that the last such Pullman Porter died in 2016.

A Personal Perspective

Without the above history, it is easy for people exposed to more impersonal services such as Uber and Lyft to take for granted an association of persons whose sole job was to accommodate the comfort of others. However, I would like to share with you what I personally know of this cadre of professionals, the Brotherhood of Pullman Porters (formerly the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters/BSCP), one of whom was epitomized and personified by my dad, Edwin Elijah Dorsey.

“Ed,” as my dad was affectionately called by his close friends, was born on April 15, 1923 in the deeply-segregated Southern city of New Orleans. He married my mother, Alberta Royal Dorsey, on August 6, 1942. However, because of the prevailing educational and employment winds of that time, all Ed was able to obtain were menial jobs—until he became a proud Pullman Porter. (“Proud,” because the job afforded him a chance to provide a safe, secure, and promising future for his young family.) I only came to recognize and appreciate the true intestinal fortitude (as in guts) and foresight (as in the early recognition of opportunities) of my dad after I became an adult.

I didn’t realize how much courage it took for my then seventeen-year old dad to secure a job with the railroad as a Pullman Porter in New Orleans in the early 1940s. Even more remarkably, the courage it took to move his wife and two daughters from Louisiana to Portland, Oregon four years later—a place where he had no family and only knew a group of Pullman Porters. The move was made with only a suitcase, the clothes on their backs, and the promise of a one-bedroom apartment in Portland.

Ed had a commitment from the railroad that he could keep his job as a Pullman Porter—with some “runs” (work assignments) between Louisiana and Portland. The runs, however, turned out to be long, and frequently had detours as far east as New York and as far south as Florida. The assignments kept my dad away from the small apartment, from his wife, and from his then three daughters for weeks at a time.

Because my parents did not have any family in Portland, my dad’s approximately twenty-five fellow Pullman Porter friends and their families became our family and we, theirs.

A brief overview of my dad’s foresight was, as a teenager, he had the wisdom to understand that there was not much hope for a “colored” young man who had not completed high school to successfully raise a family in segregated Louisiana. However, during his long trips on his railroad runs, he would voraciously read every newspaper, magazine, and book that he could get his hands on during his few non-working hours, learning and recognizing that Portland may hold hope for him and his family (which grew to five girls and one boy). Ed began reading to his children at an early age, instilling in all of us the importance of reading, the importance of education, and the importance of working hard for what we wanted. He had no idea how we would get there but he always proclaimed that we would all go to college.

My dad made every effort to expose us to as many places and opportunities as he could. Most of our visits were to places that he had read about. We rarely saw other Black families at these places, and we received stares and questions from Whites. We went to libraries, Mount Hood, beaches up and down the Oregon Coast, the Pendleton Roundup, the Grotto, farms, parks, gardens. In true Pullman Porter style, we were always scrubbed, shinned with Vaseline, and wearing our best clothes, starched stiff and ironed. (When young, the girls always had beautiful ribbons in our hair!) Throughout my childhood, the Pullman Porters served as a large part of our social outings, including completing projects to improve their families’ living quarters, landscaping yards, and so on.

For my family, the Pullman Porters built two bedrooms in the attic of our small two-bedroom home.

And over the years they built what was called a “party room” in our basement, as well as a detached, concrete one-car garage. Similar projects were completed at the homes of other Pullman Porters—always with at least one person from the group of doing the designing, framing, and building while the children pulled nails from used lumber, stacked supplies, swept, or whatever other tasks needed doing.

A Summary of Thoughts

The Pullman Porters had a bond that was focused on improving life for themselves and their families. They had a profound impact on defining loyalty and community, infusing strong work values in their children emphasizing the importance of education. I will forever be grateful to this group of men and their families (our extended family) and to my dad, as will my five siblings—all of whom either received a minimum of a bachelor’s degree and/or technical training, and experienced successful careers thanks in no small part to the influence of this group of extraordinary men.

Ethelda Dorsey-Burke made a generous gift to Bernard and Shirley Kinsey as a result of The Kinsey African American Art & History Collection exhibition at Tacoma Art Museum. Edwin Elijah Dorsey’s Pullman Porter uniform is now a permanent piece of the Kinsey family’s growing collection celebrating the achievements and contributions of Black Americans from 1595 to present times.